History of Concrete

To understand why P+Ex was formed, we first need to understand the history of concrete.

Consider the concrete dome of the Pantheon in Rome, built from concrete using natural form of cements by the emperor-engineer Hadrian almost two thousand years ago and visited by millions of awed tourists each year. And it still keeps the rain out.

In the rest of the world, concrete is everywhere. You are probably reading this in a building supported by a concrete foundation and never give it a thought. Your municipality provides basic services through concrete pipes and tanks and roads and bridges, and all that functions year after year without much notice.

Concrete is strong under compression loading – pushing or pressure – but weak in tension – pulling or tugging. Because of that, for concrete structures to function, we add steel to them. The steel resists the tension loads and lets us build bigger structures with longer spans, greater capacities and leaner cross sections. Although reinforced concrete has transformed the modern-day built environment, we must contend with the drawbacks associated with steel embedded into concrete. Unfortunately, steel is made from metals that corrode in the presence of moisture and oxygen. That corrosion expands the embedded steel which cracks the concrete, eventually creating spalls and delamination – and possible loss of integrity and need for repairs.

Steel corrosion is the most common reason for concrete deterioration – there are a bunch of other causes which we can get to at a later time. But it’s why you see rusty concrete when you drive under a hundred-year-old bridge, or trip over a what looks like a nick in a sidewalk. This deterioration can be prevented, but if it has already happened, the structure can be repaired and preserved. The concrete repair industry is a $40-50 billion a year endeavor in the US alone. Other than addressing safety and continuing serviceability, concrete repair preserves the energy that was used to build the structure in the first place.

BACKGROUND

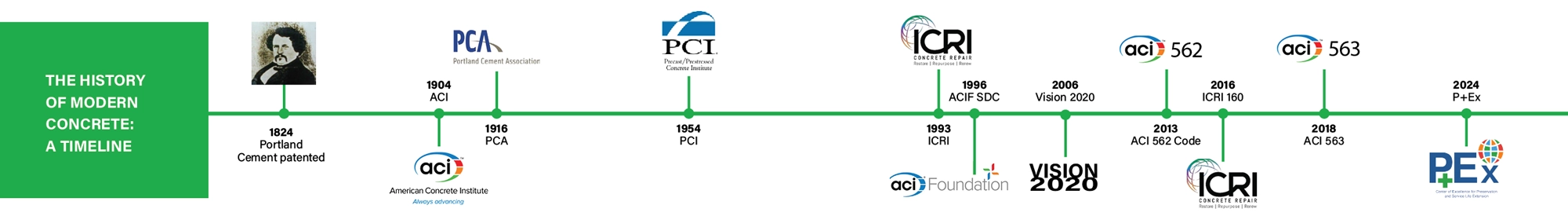

Portland cement, the miracle substance that makes concrete possible, was patented in 1824 by bricklayer & mason Joseph Aspdin in Leeds, England.

Mr. Aspdin had a kiln in his backyard and somehow serendipitously burned some clay and limestone together one day and came up with a bunch of rocks (called “clinker” today) that, when ground down into a powder, created a material (cement) that has much higher strength than the natural cements used in traditional masonry mortar. So just over 200 years ago, modern concrete was invented.

It took nearly 50 years, for Portland cement, patented by Joseph Aspdin in 1824 to become a common building material. By 1886, concrete was understood well enough for the Statue of Liberty to be placed on a colossal mass concrete foundation that still, unseen by the public, supports the monument today. In 1904, the American Concrete Institute (ACI) was founded, followed by the Portland Cement Association (PCA) in 1916 and Precast/Prestressed Concrete Institute (PCI)

in 1954.

These organizations managed the concrete construction industry for decades, creating guidelines, standards and codes for the safe construction of concrete structures. (Additionally, more specialized groups have been created over the years, such as the Prestressed Concrete Institute, etc.) However, the industry lacked standards for maintenance and repair of concrete structures – there were no guidelines for how and when to intervene in a structure’s deterioration process and keep it in use in a safe manner.

In 1988, at a World of Concrete seminar, people who specialized in concrete repair came together and shared their concerns about this lack of standards and guidelines for concrete repair. In response, the International Association of Concrete Repair Specialists was formed later that year.

In 1993, the name was changed to the International Concrete Repair Institute (ICRI). About a decade later, in 2005, Vision 2020 was published, an all encompassing initiative to make the concrete repair business more effective, efficient, and sustainable, by the year 2020.

As these efforts have developed – ACI 562, a codewriting committee, published the first version of a building code in 2013, and ACI 563, a committee for repair specifications, published its first standard in 2018, and just published a revised and greatly expanded version in the spring of 2025.

In a great achievement, ACI 562 has been adopted by the International Existing Building Code as of 2022. ICRI established its Sustainability Committee 160 and published a white paper to address the intrinsic value of our existing concrete environment in 2016.